BBC Maestro’s Masterclass in Creeping Everyone Out

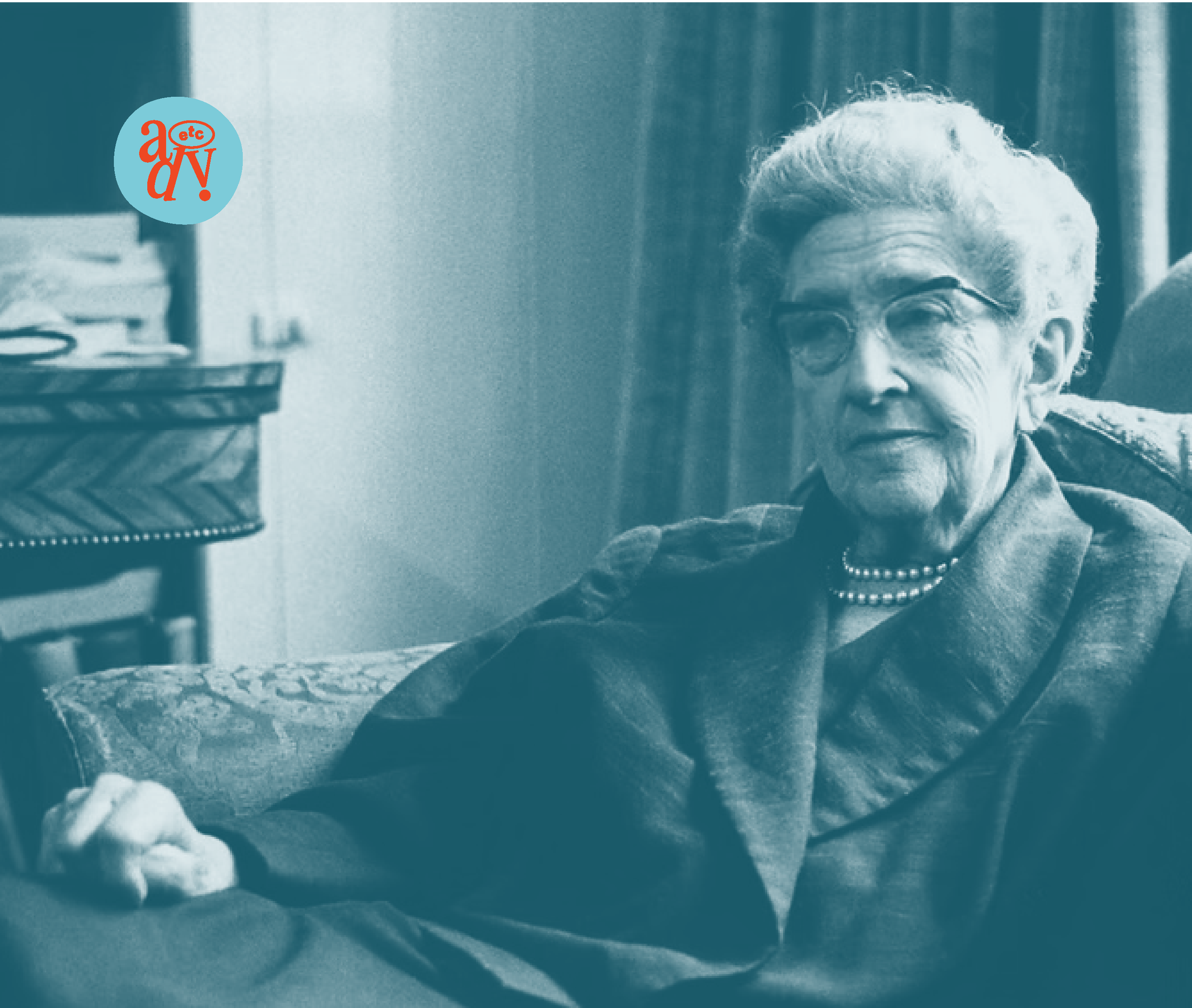

In creating the uncanny likeness of Agatha Christie and positioning their course as a chance to learn from the deceased Queen of Crime without disclosing the use of AI, BBC Maestro has created a near-universally reviled automaton that degrades the education platform’s entire offering.

Nobody wants AI Christie

It’s no secret that I’m an Agatha Christie megafan. My encyclopedic knowledge about and obsession with the author began in my early 20s, when her novels provided an escape from my not-fab inner world.

So, when a BBC Maestro ad popped up in my Instagram feed, Agatha Christie’s voice was familiar enough to make me stop, watch and wonder where this new-to-me archival interview content had come from. Christie wasn’t interviewed much. There’s a BBC radio interview from 1955, and she’s written about her process – but she was famously private, often letting her writing (particularly under her pseudonym, Mary Westmacott) speak for her.

In the video, Agatha Christie’s AI-assisted face floats, pale and flat, on someone else’s body, her mouth moving in sync with an actor’s voice, speaking words that BBC Maestro claims as her own. It’s a deepfake, even if the author’s estate rejects the use of the word, citing their consent to the project and consideration for ‘ethics’.

It gave me the creeps big time, and a quick glance at the comments showed that I was far from alone.

The stats (sorry statisticians)

While I’m interested in the ethical implications of estates controlling likenesses of the deceased, I’m equally interested in why BBC Maestro’s audience has so roundly rejected Agatha Christie On Writing.

Over 4 days, from 30 April to 3 May 2025, the learning platform posted 9 times on Instagram about this course. On 6 May, I reviewed every comment under each video, categorising them as approving, disapproving or neutral and noting key concerns. Here’s what I found:

58%

disapprove of the course

32%

approve of the course

9%

just want to talk about Agatha Christie (iykyk)

Most people hate it

Unsurprisingly (to me, at least), most people hate the idea. And they don’t just mildly dislike it – posts expressing disapproval are, on average, 2.25 times longer than those expressing admiration. Approving comments average around 40 characters, while disapproving ones come in at about 90. People who dislike the concept have a lot to say, and those who like it often respond with just emojis. In fact, 45 per cent of the approving comments are emoji-only – which raises questions about bots, but we’re taking the data at face value because I’m not built for that sort of maths.

2.25x longer

disapproving comments are 2.25 times longer than others

45%

of approving comments are emoji-only 🫠

Among the comments that disapprove of the concept, three main objections have emerged: the use of AI (particularly for visuals), the content’s unsettling nature and a concern for Agatha Christie’s personhood and legacy.

Of the disapproving comments:

38%

explicitly object to the use of AI

21%

find the content disturbing, disgusting or creepy

21%

express concern for Agatha Christie’s personhood and legacy

38 per cent of disapproving comments object to AI

Of those disapproving, the most significant area of concern is the (mis)use of AI. It’s worth noting that while the BBC Maestro course page discloses that it contains ‘audio and visual AI enhancements’, no such disclosure appeared in any of the Instagram posts.

Comments range from a general dislike of AI – for ethical, creative and environmental reasons (‘AI takes SO much energy and the planet is suffering enough’) – to disappointment that BBC Maestro didn’t stick with a human actor. A number of commenters say they might have been on board with the concept had BBC Maestro not overlaid the AI face on top. These objectors left comments like ‘Use a real person or don’t do it at all’ and ‘The voice actor, or an actor, or modern authors would have been enough’.

People find it ironic, frustrating and disrespectful that BBC Maestro is attempting to sell a course on creativity with an AI teacher. A number of comments agree that ‘AI doesn’t belong in writing or the creative process’, while others support the use of actors but not AI, saying, ‘Use a real person or don’t do it at all.’

“AI doesn’t belong in writing or the creative process.”

There is also deep concern about consent, despite the videos stating that the content was created with the support of Agatha Christie’s estate and Christie scholars. Many feel that this isn’t enough, and that it explicitly goes against what they assume to be her wishes. Some question the legality of the process, mentioning that ‘she was very careful of her privacy’ and that ‘she never gave her consent to this’.

“She never gave her consent to this.”

Overall, there is a palpable feeling of exhaustion at ‘yet another’ AI product, coupled with concerns about consent, ethics and the power of estates. Notably, 11% of disapproving comments mention the perceived cupidity of the Christie estate, referring to the course as ’tacky’ and ‘a cheap, gimmicky cash-grab’ that ‘shows the sheer greed of those responsible for her estate’. Yikes.

21 per cent of the disapproving comments find the concept disturbing

Across many comments is a sense of deep discomfort and dislike for the AI Agatha Christie. Many people find the uncanny valley visuals disturbing and express this with terms like ‘unsettling’, ‘ghoulish’, ‘disturbing’ and ‘scary’. Meanwhile, other commenters can’t pinpoint why they dislike it so much, but share that they ‘just don’t like it’ and that ‘this should be a crime’.

“This is more scary than all the murder in her books.”

21 per cent of the disapproving comments express concern for Agatha Christie’s personhood and legacy

Finally, and closest to my heart, are those who object to the course out of respect for the famously private woman’s personhood and legacy. There is a strong sense of injustice and violation – ‘a famously private person’ ‘forced out by AI’ and puppeted without their consent, after their death, to support whatever cause an estate may see fit.

“A famously private person dragged into this to sell a ‘course’.”

There is also emphatic commentary from those who feel the course desecrates her humanity, career and legacy. It is here that language becomes particularly impassioned, with one commenter saying, ‘You are abusing a dead person’ and another saying that BBC Maestro are ‘vile people’ for letting this happen. It speaks to the profound sense of immorality raised by this technology – seen as a form of digital necromancy – that some commenters were so disgusted they unfollowed BBC Maestro. One states, ‘This is disgusting and I can't even look at this page anymore’.

“It is a slap in the face of her hard work, her mind, and her right as a human being to speak for herself.”

People are passionate about Christie’s work and legacy, and for many, Agatha Christie On Writing is seen as contemptuous and ‘an insult’ to both fans and the author. While some connect with the AI Christie, others are repulsed, saying, ‘Agatha Christie turning over in her grave’ and ‘She would’ve loathed this’.

We long for a connection that AI can’t mimic

BBC Maestro’s attempt to resurrect a facsimile of Agatha Christie to sell a writing course was a catastrophic miscalculation – not just creatively but ethically and strategically. The backlash has been a masterclass in how profoundly a company can misjudge the appeal of an author and what audiences genuinely seek from creative education. Christie’s work is often dismissed as formulaic, using flat, archetypal characters to tell the same story on repeat. While somewhat true, the greatest writers in history have harnessed the power of archetypes as a shortcut to the story itself, and nobody is questioning Christie’s ability to write a rollicking tale. Her faults – which mirror those of many figures of her era – are racism (both benevolent and openly hostile) and sexism, which manifests occasionally as clever and resourceful women finding their true position in life through marriage to the only man who can best them (I’m looking at you, Anne Beddingfeld).

Yet despite these ‘flaws’ in the real person, the overwhelming sentiment is clear: readers don’t want a digital marionette, dangling someone’s filtered likeness on the end of a string. They want a real, human connection – even when the author is long gone and fallible. There are no shortcuts to that connection.

Collecting this feedback has been a relief – not because it was universally damning, but because it reaffirmed what most of us instinctively know: creativity is an inherently human pursuit, and our connection to authors, even posthumously, is rooted in the truth of their work and the legacy of their experiences. Readers, writers and students read and write to connect with real people. And no algorithm can replicate that genuine human insight, no matter how convincingly it appears to mimic the dead.