Sorry, You Can’t ‘Sound Like Attenborough’

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in The Metamorphosis Project Journal 2025 issue, Vox: Cartographies of Voice and Power.

As a copywriter – and someone who’s spent hours teaching students that voice isn’t something to be shrugged at – I’ve dedicated a decent chunk of my career thinking about, arguing over and defending voice. Brand voice, I tell my clients, will transform your paragraphs from utilitarian text into something with life in it! Get it right, and your words will leapfrog the competitors’ dreary bleating and land squarely in your customer’s ear. Voice is a powerful thing.

Yet although copywriters agree on this point, the degree to which it’s possible to define written voice is one of the Great Questions of Copywriting™. To what extent can we create a set of rules that, once written down, allow anyone – regardless of medium, brief or mood – to reproduce a voice convincingly? Which brings me to one of the most common requests I get from environmental brand clients: “Can you make us sound like David Attenborough?”

As a branding goal, it makes sense! Voice is a powerful instrument for science, and there are few voices in the world as recognisable as Sir David Attenborough’s. As a communicator, he is sui generis – in a class of his own – adored by laypeople and experts alike. The public loves him for his wit and warmth and for making complex ideas feel clear, wondrous and accessible. Scientists love him because he was often the first stepping-stone in their careers – a gateway drug to messing around in mangroves – and because, crucially, he never flattens the nuance. He knows his stuff, and he respects his audience enough to assume they can too. Most importantly, he interrogates humans’ relationship with our planet and invites us to do the same. Attenborough’s voice, with its combination of scientific rigour, awe and inclusivity, hits the perfect note for environmental storytelling. What brand wouldn’t want a piece of that?

“Attenborough’s voice, with its combination of scientific rigour, awe and inclusivity, hits the perfect note for environmental storytelling. What brand wouldn’t want a piece of that?”

Of course, there’s a snag. Environmental brands’ audiences are, more often than not, the same corporations whose land clearing and fossil fuel projects made reforestation necessary in the first place. Their survival depends on staying in the good books of destructive companies while also repairing the harm they’ve done. Their voices are stuck walking a tightrope. Meanwhile, Attenborough’s voice – inseparable from Attenborough the human, untethered from corporate stakeholders and buoyed by a lifetime of personal conviction – can speak freely. His voice is his own and therein lies its irresistible power. Brands are non-human entities entangled in stakeholder politics. The people within them can admire Attenborough, but as we’ll learn, the brands themselves struggle to mimic him.

Defining voice

To understand why Attenborough’s voice is so maddeningly difficult for corporate brands to borrow, it’s helpful to define ‘voice’ in a brand context. The good news is that you’re already an expert. Humans are natural communicators, and most of us are highly attuned to recognising tone and message in writing. We can identify people’s mood, intentions and values not just by the sound of their speech, but through the writing choices they make. You can tell that your friend is upset by the full stop they put at the end of a text (‘I’m okay!’ = they’re okay; ‘I’m okay.’ = doom). An emoji can transform an icy work email into something almost chummy. ☺️

In copywriting, we can develop and implement a brand’s voice by thinking of the brand as a person. Its visual identity shows us what that person looks like, and its verbal identity tells us how they sound. A brand’s voice is a cocktail of what’s said (the content) and how it’s said (the grammar, rhythm, punctuation, etc.). These decisions shape not only voice but how audiences perceive a brand’s character, intent and credibility. Trumpian exclamation marks, for example, have the power to tip the tipple from dignified to downright silly.

“But here’s the rub: although we build brand voices with a person in mind (and surprisingly often that person is Hugh Jackman – the man’s charming!), brands aren’t actual people. ”

But here’s the rub: although we build brand voices with a person in mind (and surprisingly often that person is Hugh Jackman – the man’s charming!), brands aren’t actual people. They’re entities that must maintain a socially constructed performance of professionalism in order to gain and keep clients. What counts as ‘professional’ varies by industry, audience and context, but in today’s environmental agencies, it often means sounding objective and scientific. Passionate, but not sentimental. Deeply knowledgeable about biodiversity, but careful not to assign blame for its decline. Attenborough’s voice can reflect his undiluted worldview because he’s a person, not a leadership team armed with brand guidelines, and he’s free to express his values through linguistic choices. Once you learn to tune your ear for those choices – relationships, pronouns, metaphors, rhetorical flourishes – it’s impossible to unhear them.

Learning to listen

I’m a copywriter now, but I’ve been writing in one form or another my whole life. I grew up in a family that loves books and pays close attention to the natural world. Those early influences shaped my personal grammar and, therefore, how I approach writing for clients about nature and science.

My granddad, ‘The Mad Axeman’, is a bush poet and legend in Western Australian bushwalking circles. He can recognise a stretch of the 1,000km-long Bibbulmun Track from a rock that looks to the rest of us like (sorry Granddad) a rock. He would vanish for weeks into the bush, often with only the landscapes for company, returning skinny, hairy, smelling of cheese and having written a poem about the adventures of a lusty pig. When I stayed with my grandparents at their farm, I was given two duties: ferrying out a tray of water for the wild bees – a terrifying responsibility – and leaving scraps for the butcher birds. One of my uncles is a bushfire fighter, another worked in animal husbandry and the third lives with an assortment of animals, including Nigerian Dwarf goats and a flock of geese whose egg-laying is so capricious that their only reliable collectors are crows. One summer, I was roped into measuring this uncle’s orchard across a hillside so each tree would receive maximum water via natural drainage. A tedious chore, but an undeniable exemplar of my family’s values.

Meanwhile, my parents, who live in Singapore, help care for the colony of drain cats outside their apartment. This practice is common for many Singaporeans, who see drain cats as valued members of the community whose survival depends on human responsibility. In family chats, we share photos of wild otters, hornbills and giant ferns erupting from drains. (Mum also requested that I mention her spotting of a civet cat – an eviable feat!) This is all to say that the natural world is interesting to us, and we consider ourselves responsible members of it.

“The natural world is interesting to us, and we consider ourselves responsible members of it.”

Alongside this lived education, I grew up reading naturalists whose voices shaped my understanding of humans’ relationship with the natural world. Gerald Durrell’s superb, shambolic memoirs (who can forget the Rose-Beetle Man?) and Konrad Lorenz’s King Solomon’s Ring taught me that curiosity, reciprocity and cohabitation with animal subjects are not incompatible with rigorous scientific observation. Like my family, these writers didn’t sentimentalise the animals they wrote about but treated them as fellow beings. Care and compassion were always paired with realism, including the decision to end suffering where necessary.

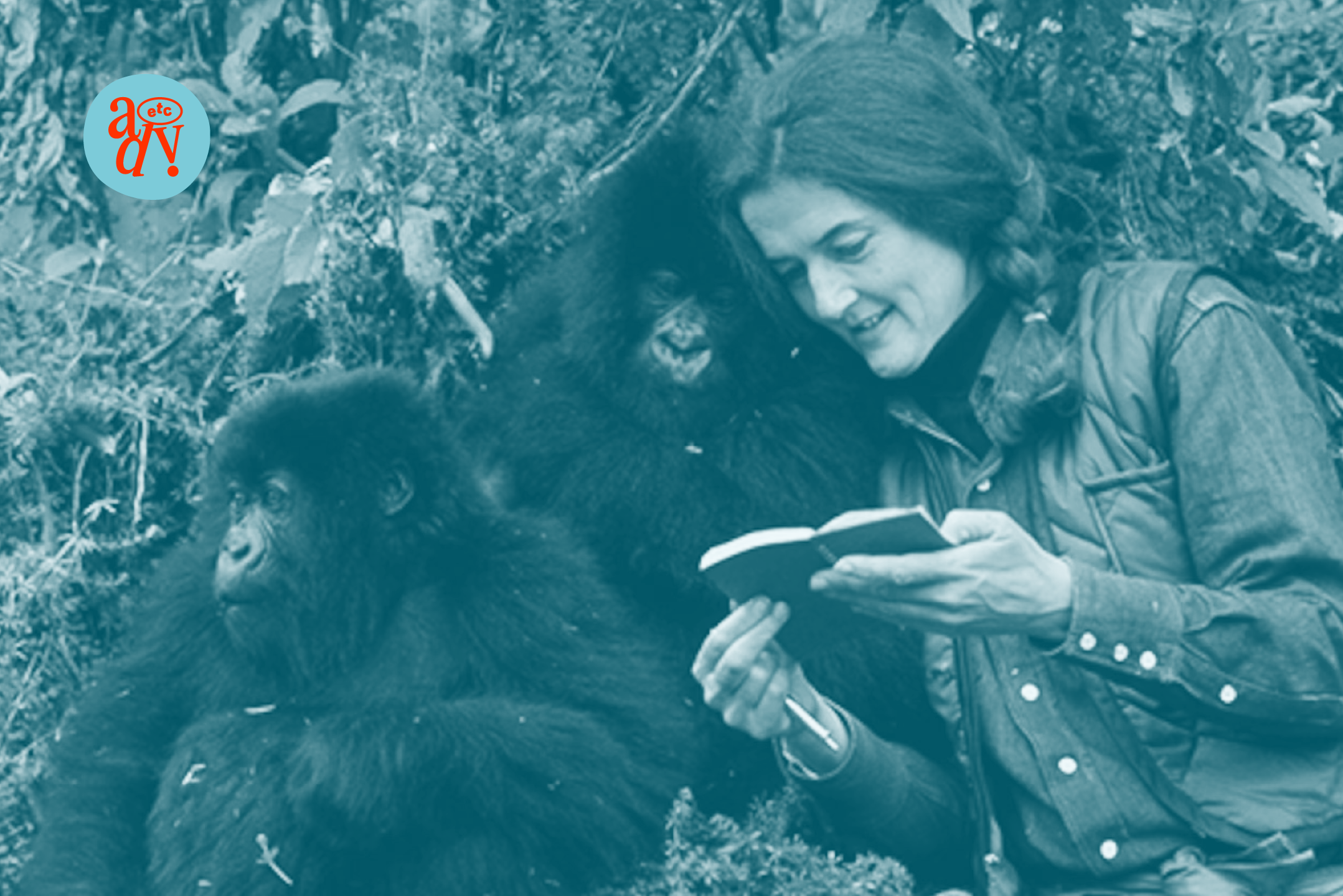

As I learned to be a copywriter and became more attuned to the nuances of voice, I realised that the naturalists I most admire – Attenborough, Durrell, Lorenz, Carson, Goodall, Audubon and Fossey – all share a voice that recognises humans as part of the natural world, not separate from it. We inherit its gifts, yes, but also its obligations.

This perspective isn’t unique to naturalists. It is foundational to Indigenous philosophies across the world, which have always placed humans within ecosystems, not above them. Only recently has Western science caught up, dusted itself off and started exploring this revelation. Attenborough’s voice expresses what has always been known: the supposed division between humans and nature is both artificial and disastrous.

Voicing values

Attenborough’s voice may feel distinctive now, but it’s really part of a much older tradition sometimes called ‘nature writing’. The genre predates the buttoned-up objectivity of modern science writing by centuries, its lineage stretching from Attenborough’s writing to those well-thumbed childhood books I adored and as far back as Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species. Nature writing isn’t defined by the what (mountains, fungi, water snakes chasing marine iguanas) so much as the how. It frames the relationship between people and the natural world, and the stylistic choices it uses give that relationship voice. If science writing is, as Potawatomi botanist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer calls it, “a language of objects”, then nature writing is the language of relationship. It assumes that the other beings of the natural world are not objects (animate or inanimate) but active subjects, characters with agency, lives and experiences of their own. This way of looking shapes how nature writers communicate.

“If science writing is, as Potawatomi botanist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer calls it, “a language of objects”, then nature writing is the language of relationship.”

Writer and scientist Sarah Boon suggests that science writing and nature writing sit on opposite ends of a continuum. At the science end, the voice prioritises facts and rigour. Slide a little closer to the middle, and you get ‘human interest’. Keep going, and you arrive at nature writing, where human relationships with nature take centre stage. Traditional science writing – the safe zone most environmental brands cling to – prizes objectivity, detachment and emotional distance. For Kimmerer, who trained as a botanist, this meant that “plants were reduced to objects; they were not subjects”. Accepting this framework meant she “stepped off the path of Indigenous knowledge”.

Nature writers, on the other hand, argue that science doesn’t crumble when paired with other ways of knowing, whether that’s cultural, artistic, philosophical or theological. Au contraire, it gets richer. Nature writers, free from the constraints of science writing, happily draw on the full toolkit of literary craft: rhetoric, metaphor, narrative, personification and sentence-level choices like punctuation, capitalisation, syntax and choice of pronouns. This is where panic sets in for brands. They imagine that to write in this style is to sound ‘hippy’ – the dreaded word! What they usually mean by that is any mention of awe, art, responsibility or doing much beyond paying lip service to Traditional Custodians. All of these, of course, would make the copy far more interesting and aligned with Attenborough’s nature-writing style, but it would also be less ‘safe’.

But historically, nature writing wasn’t an unscientific affectation – it was the default approach to science communication. In Ornithological Biography, naturalist John James Audubon confidently attributes memory and happiness to ravens. Audubon’s birds are even religious, humbly praying to the “Author of their being”, who is also – poor ravens – “their most dangerous enemy”. Modern nature writers are more cautious about anthropomorphism, but they don’t swing to the opposite extreme either. They reject the anthropocentric view that humans are the only beings with relationships, inner lives, motivations, pleasures and fears. Primatologists Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey, accused of an unscientific, feminine sentimentality and anthropomorphism at the time, broke from contemporary scientific style and wrote about gorillas and chimpanzees not only as research subjects but as fellow members of a shared community.

These values are particularly alive in Indigenous nature writing. Brands are inclined to agree that Indigenous Knowledge matters, but often, they’re cautious about how to express it – sometimes because it’s not available to them, or because their ability to consult with knowledge holders is limited. Still, for those willing to express these values, the knowledge finds its way into writing through careful, deliberate choices of language. In an article comparing an Indigenous framework with Australia’s National Water Initiative, the Martuwarra/Fitzroy River was listed not merely as a subject but as the lead author, alongside two human authors. This authorship “reflects the fact that people, land and water are not separate”. Like many people in Australia, the authors (the Martuwarra, Dr Anne Poelina and Dr Kat Taylor) capitalised the Aboriginal Australian word ‘Country’ throughout, recognising it as “a living presence to which people relate”.

Kimmerer makes a similar point about language, arguing that grammar itself can either hide or reveal our ethical responsibilities:

Maybe a grammar of animacy could lead us to whole new ways of living in the world … a world with a democracy of species, not a tyranny of one—with moral responsibility to water and wolves, and with a legal system that recognizes the standing of other species.

Her suggestion is eminently practical! The lead authorship of the Martuwarra is one expression of a growing movement to recognise the personhood of rivers, led by Indigenous peoples across the world. This movement understands that the words we use to describe natural beings – whether rivers, birds or mountains – are never just words. To call a river ‘it’ makes them an object; to call a river a being places them within a network of obligations and respect. Once you see a river as a fellow being, it becomes increasingly difficult to go on polluting and carving it up without a pang.

This voice and perspective can feel dangerous for brands used to the safe, air-conditioned atmosphere of Western scientific authority, but Attenborough’s voice embodies these same values. He opens the windows, lets in the breeze and frames nature as kin, not commodity. When Attenborough met Fossey’s gorillas, he despaired at their reputation as “brutal wild beasts” because “they were our cousins and we ought to care for them”. He’s called the natural world “a key ally” – an active partner in survival, not a storage cupboard of resources to raid when the mood strikes us. Again and again, he refutes the idea that the earth is ours to exploit: “We do not have a special place. We are not the preordained and final pinnacle of evolution. We are just another species in the tree of life”. He laments that humanity has shifted “from being a part of nature to being apart from nature”. That one word has catastrophic consequences.

“This voice and perspective can feel dangerous for brands used to the safe, air-conditioned atmosphere of Western scientific authority, but Attenborough’s voice embodies these same values.”

Most environmental brands would nod along with all of this in principle, but they rarely express these values in their brand voice. At best, the sentiment languishes in a vision statement nobody reads. At worst, it’s not there at all. And that’s a deep shame, because nature writing isn’t indulgent or sentimental; it’s a legitimate, rigorous approach to science communication, and the values it expresses are fundamental to Attenborough’s impact. He speaks as if our relationship with the living world matters, because it does.

And that – inconveniently for brands who long for Attenborough’s voice but can’t embody his values – is why people listen. If brands want to sound like Attenborough, they must screw their courage to the sticking place and give voice to those values. The good news is that Attenborough can show the brave exactly how it’s done.

Understanding Attenborough

Remember that a brand’s voice is a combination of what it says and how it says it. If the values of nature writing define the what of Attenborough’s voice – the worldview and priorities his work communicates – then what follows is the how. His voice is shaped by the values of coexistence, reverence, humility and responsibility, and these influence the sentence-level choices he makes. If I were to try to replicate Attenborough’s voice, I would need to express both the what (the values) and the how (the language patterns that express them so successfully). And so, in the spirit of the great man himself – crouched in the snow, notebook in hand, documenting a penguin turning to a life of crime – I went to his 2020 book, A Life on Our Planet: My Witness Statement and a Vision for the Future, to study his voice *in its natural habitat*.

I always start with punctuation, which is the gesture of writing – the nods, eyebrow-raises and hand-flourishes we make on the page. Nature writers have historically leaned on these verbal gestures to guide their readers. Audubon’s Ornithological Biography is littered with exclamation points and question marks, and On the Origin of Species contains no fewer than 330 em dashes – so much for them being cooked up by ChatGPT. We can’t literally fling our arms in despair on the page, but an exclamation mark gets the point across. We can’t tap our reader on the shoulder and whisper, Slow down, this bit matters, but a semicolon does a pretty good job.

Both marks carry weight for voice. Too many exclamation marks can feel frenetic and unprofessional (one reason science writing tends to avoid them). But skip them altogether and you risk erasing urgency. Semicolons, on the other hand, can seem fusty and over-literary if not handled with care; hardly anyone knows how to use them, and using them incorrectly will rile up those who do. No surprise, then, that environmental brands aiming for an ‘Attenborough voice’ overuse semicolons and underuse exclamation marks. Attenborough himself employs both sparingly. Exclamation marks emphasise his strongest opinions, like “Earth may be a sealed dish, but we don’t live in it alone!” and “We must rewild the world!” And he uses semicolons off-label (‘incorrectly’, for pause and emphasis rather than to link independent clauses) when the sentence could benefit from a slower pace:

It was not laws invented by human beings that interested me, but the principles that governed the lives of animals and plants; not the history of kings and queens, or even the different languages that had been developed by different human societies, but the truths that had governed the world around me long before humanity had appeared in it.

Next, Attenborough adjusts his sentence lengths for rhythm, interest and impact. Science writing, by habit, leans long: clauses piled on clauses, all very carefully hedged and precise. But the communicator in Attenborough knows when to keep it snappy. Consider the impact of this series of staccato sentences: “Yet no one lives in Pripyat today. The walls are crumbling. Its windows are broken.”. The rhythm shifts again when he moves into sentences that stretch beyond sixty words, giving his writing a rolling musicality. Long sentences invite reflection; short ones snap the reader to attention. Because there’s no room for obfuscation, environmental brands may find this a challenging way to write. To share Attenborough’s rhythm, you have to share his conviction. And that often means giving up the careful neutrality that a ‘professional’ voice tries so hard to maintain.

“Because there’s no room for obfuscation, environmental brands may find this a challenging way to write.”

Attenborough’s word choices, too, are emphatic, emotional and anything but neutral. He doesn’t hesitate to lament “our destruction”, to warn that things have gone “catastrophically wrong” or to (correctly) accuse fossil fuel users – from oil companies to superannuation funds – of “stealing” from nature. It would take a fearless environmental agency, no matter how impassioned the individuals inside it, to use this kind of language in its brand voice. After all, that voice exists largely to win and keep resources clients, who probably wouldn’t be too pleased to hear themselves called thieves.

It’s equally unlikely that environmental brands would follow Attenborough’s lead in employing words more commonly found in the vocabulary of faith than science. Like Lorenz, who describes the “magic” of nature, Attenborough employs adjectives like “breathtaking” and “extraordinary”. Brands, ever wary of sounding mawkish, shy away from these, even though emotional connection is essential to ecological storytelling. Even Darwin himself paused to admire the “beautifully plumed seed of the dandelion”. Nature writing has always allowed room for awe. Environmental brand voice, almost by definition, does not.

A final example (though hardly the last) is Attenborough’s use of rhetorical devices to sustain his tone. He uses metaphor, calling the ocean “the Earth’s life-support machine”, and scatters his work with rhetorical questions: “After all, wasn’t the ocean vast, and virtually unlimited?”. His pronoun choices speak volumes: like Audubon, who consistently used ‘he’ for ravens, and Kimmerer, who critiques the disrespect of calling living beings ‘it’, Attenborough rejects neutral pronouns: “Like all leopards, she hunts on her own”. Capitalisation, too, is an expression of his values. By writing ‘Sun’ and ‘Earth’, he echoes Lorenz, the Martuwarra, Taylor and Poelina, who capitalise ‘Nature’ and ‘Country’ to signal presence, agency and respect.

Attenborough’s voice is only the visible tip of the iceberg. Beneath the surface lies the weight that keeps it afloat: his knowledge of the natural world, his personal values and the endless micro-choices in language that express those values. Brands – understandably enchanted by the visible part – want to mimic it. But without the mass beneath, the imitation is superficial. The iceberg quickly melts.

Shaping voice

It’s hard to list these qualities to a brand eager to sound like one of its scientific idols without slipping into a cut-price version of Kipling’s If—. If you can hold your values steady despite stakeholder pressure; if you can express awe of the natural world when convention tells you it’s unscientific; if you can admit our role in damaging the planet in order to help it heal; if you can drop the performance of professionalism and confess that you are human; then you’ll have a voice like Attenborough’s, and – what’s more – you’ll understand it!

Brands often say they want to sound like Attenborough. What they’re really after is the effect of Attenborough – his authority, charm and ability to connect us with our world – without the messy, inconvenient necessity of voicing his values. And there’s no shame in that. Most brands are run by perfectly decent people who, if given half a chance between budget meetings and quarterly forecasts, would happily embrace those values. But brands aren’t people; they’re commercial entities doing their best to appear warm and wise while relying on profit and compromising as a result. A brand can try to borrow Attenborough’s cadence, but it can’t borrow his convictions. A brand can’t mimic his voice because it’s inseparable from his humanity. You can’t sound like Attenborough if you don’t believe as he does. His values shape his voice.

So here’s what I tell brands who ask me to make them sound like Attenborough: let your brand voice wander as far as the constraints of your organisation will allow. Find the voice that is sui generis to your brand – incomparable, because what you do and how you do it is, by default, unique. And where you can, as a person not a brand, let your human voice out for a stroll. Allow Attenborough’s influence to guide you, but don’t copy him. Let your words carry the values you truly believe in, and trust that your own rhythm, care and curiosity will carry the rest. If you get it right, your voice won’t sound like Attenborough’s or anyone else’s. It will sound like something even more wonderful: You.